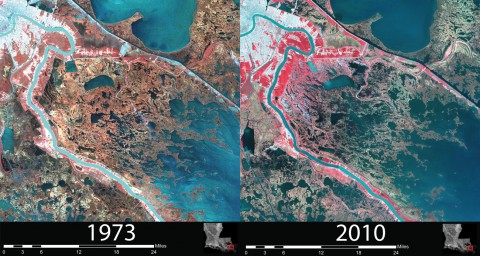

Louisiana will lose 1,750 square miles to the ocean over the next 50 years as sinking soils, rising sea levels, and man-made developments continue eating away at the coast. That is nearly nine times what Hurricanes Katrina and Rita swallowed in 2005, and almost as much as what has vanished in roughly the last century.

“Louisiana has 40 percent of our nation’s wetlands, but we are experiencing 80 percent of its loss,” said Jerome Zeringue, chairman of the state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority.

The quickly eroding oceanside prompted state officials in 2012 to approve a $50 billion, 3,000-page master plan developed by the authority to restore and protect Louisiana’s coast. It is the largest wetlands effort the state has ever undertaken, Mr. Zeringue said.

That plan is largely dependent on money the state does not have. Instead it is relying on federal funds and future revenues not yet secured, including oil and gas royalties expected in 2017.

About $2 billion has been spent to date on several projects, including construction of 59 miles of new levees and restoration of 32 miles of barrier islands.

Despite such projects, some like Mark Davis, a senior research fellow at Tulane University, question whether enough can be done to stem the tides — especially at the pace at which the state is moving.

Based on predictions from the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, Louisiana is expected to lose 35 square miles of coast per year, but only plans to restore up to 16 square miles annually.

Mr. Davis, director of the Tulane Institute on Water Resources Law and Policy, likened it to “me having a heart attack and deciding I’m only going to drink two milkshakes instead of four. I made a change. But I haven’t necessarily made a difference.”

While some pieces of the preservation effort are fairly routine, such as constructing protective levees, other ideas are less proven.

For example, the plan calls for opening up the Mississippi River in several places to allow some of its fresh, sediment-rich water to feed dying wetlands. Over time, state scientists believe, the sand, silt and clay in the water would build up, helping to restore surrounding marshes. Levees around the river have kept the sediments from flowing freely to surrounding areas, instead forcing them into the Gulf of Mexico.

Natalie Peyronnin, a scientist who helped the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority develop its master plan, said opening the Mississippi in key areas would help correct past mistakes made when the river was originally blocked off.

“Because we are in such an urgent land loss situation, we need to take action quickly,” Ms. Peyronnin said. “We also need long-term sustainability.”

Design of the first opening has begun, but state and federal permits for the project still need to be obtained.

Torbjörn Törnqvist, a Tulane researcher who has studied sea level rise in Louisiana for almost 15 years, said he was unaware of a similar water diversion project.

“It is true that this is somewhat uncharted territory,” he said. “No question there will be surprises and some unexpected outcomes. That is not an argument to call it off, in my mind.”

But George Ricks, a commercial fisherman from St. Bernard Parish, said he fears that significantly rerouting Louisiana’s waterways will destroy his livelihood by releasing large amounts of freshwater into salt marshes. Mr. Ricks created the Save Louisiana Coalition to lobby against the proposed changes, which he argues would overwhelm the land, devastating oyster beds, as well as shrimp, crab and trout populations.

“If they totally freshen this estuary, the species won’t be able to reproduce,” Mr. Ricks said. “They don’t know what these things will do. It’s never been done before.”

Rather than opening up the Mississippi and allowing it to run into salt marshes, Mr. Ricks said his group supports rebuilding the wetlands by pulling up sediment from the river bottom and redepositing it elsewhere. The state’s coastal restoration authority says that would be too expensive.

Louisiana officials say they are planning to finance coastal conservation projects using numerous sources, such as surplus state funds and settlement money received as a result of the BP oil spill in 2010. They are also expecting about $80 million a year from a federal coastal wetlands program and roughly $110 million a year from the federal Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act, which provides payments to Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas from oil and gas developments.

Despite the billions it plans to spend, Louisiana’s coastal master plan leaves some issues unaddressed.

Some of the state’s expected land loss, for instance, will come as area soils sink, a problem that has been accelerated by oil drilling and other activities that remove water from the ground, Mr. Davis said. The most affected parts of New Orleans are sinking by more than an inch each year, according to estimates from a study published at the journal Nature.

“We pumped the water out of the soils,” Mr. Davis said. “And as anybody who goes camping knows, if you carry dehydrated food, they weigh a whole lot less than foods that still have water. That’s how our soils are.”

Mr. Davis helped develop a proposed $6.2 billion project — separate from the master plan — that over the next 50 years would add new drainage systems, canals and storage lakes to the state’s water retention system, which would absorb flood water and keep underlying soils moist instead of pumping it all out.

Even if the master plan and other projects are successful, experts say the state remains at risk of losing itself as climate change contributes to rising sea levels. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts that if nothing is done, ocean waters could rise up to 6.6 feet by the year 2100.

Mr. Törnqvist says that means the state’s master plan may be just a Band-Aid.

“If we implement that plan really, really well,” Mr. Törnqvist said, “we may buy a couple of decades to build some new land, but it’s not going to last.”